Productivity, as defined originally in economics, is a measurement of the rate of output per unit of input. It didn't take long for that concept to spill over to popular culture in the form of "Personal productivity," which is really a measure of how efficiently and consistently a person can complete an important task.

Unfortunately, the concept is often misinterpreted and misjudged. We assume the more stuff someone can cram into a day, the more productive they are. Dead wrong. And unfortunately, quite a dangerous assumption, which is why the productivity movement is undergoing an existential crisis of sorts right now.

Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. Albert Einstein.

What good will I do this day?

One of the pioneers of personal productivity, way before the term entered our modern lexicon and became ubiquitous, was American polymath Benjamin Franklin. Known later as the "harmonious human multitude," Franklin had always shown an interest in both societal and self-improvement.

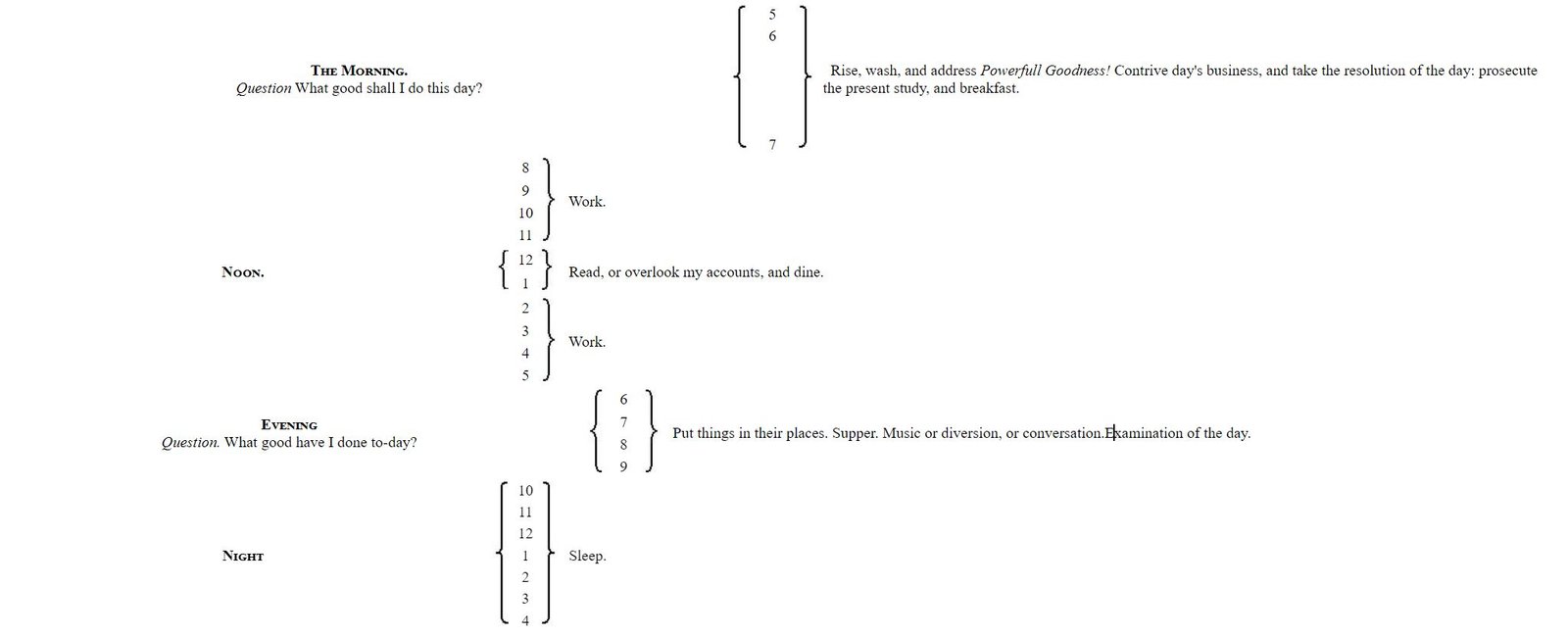

In Franklin's autobiography, published by Project Gutenberg, he is famously known for bookending the start and end of his days with two questions:

Franklin started his day with "What good will I do this day?" and ended it with "What good have I done today?" Between these two questions, he carefully scheduled hours for work, chores, and reflection.

Franklin's schedule. P.C.: Project Gutenberg

From the accounts we have of Franklin's life and his contributions to society, it's safe to assume that such a regimented approach to using time seemed to work for him, though it wasn't without issues.

Not always rosy

Like most people trying to optimize their personal productivity, Franklin had his own share of frustrations. His carefully crafted daily schedule would be thrown off because he couldn't find the right information at the right time. Franklin's Achilles Heel? His organizing skills left a lot to be desired. In his own words,

Order, too, with regard to places for things, papers, etc., I found extremely difficult to acquire.

In a later commentary, American historian Professor John Bach McMaster alluded to Franklin's struggles with staying organized. "Strangers who came to see him were amazed to behold papers of the greatest importance scattered in the most careless way over the table and floor."

That said, Franklin made peace with the situation. He realized he had lofty goals, some of which would never be realized. But he believed he was better off trying to incorporate ambitious personal productivity techniques into his life than giving it up altogether.

On the whole, tho' I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavour, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it.

What productivity is not: Making every second count

A lot has changed in the world from how things were during Franklin's time. One of the more blindingly obvious changes has come in the personal productivity space. Fueled by external and internal expectations, we now live in a culture where there's pressure to make every second of our life count.

And, in that regard, we set the bar ridiculously high.

We reserve our right to call someone successful unless they create companies that make it to Crunchbase's startup database with at least three rounds of funding AND can bake the perfect braided multigrain loaf of bread while ALSO running ultramarathons, you know, over the weekends, in their "spare" time.

As a result, we are now squarely entrenched in what has become known as the hustle culture. We overwork to the point where work-life balance becomes a joke.

Hustle culture

In a 2016 interview with Bloomberg, when she was still head of Yahoo, Marissa Mayer caused an uproar when she hinted that working 130 hours a week at your job shouldn't be seen as too farfetched an idea.

Could you work 130 hours in a week? The answer is yes, if you're strategic about when you sleep, when you shower, and how often you go to the bathroom. Marissa Mayer.

Not to be outdone, Tesla founder Elon Musk contended that nobody changes the world at 40 hours a week and that it takes 80, maybe even 100 hours of working every week to make an impact.

Sadly, this isn't hyperbole solely intended to attract eyeballs on Twitter. We seem, as a culture, to be glorifying and rewarding the "I'm wedded to my work" culture without acknowledging the elephant in the room: Cut it any which way. It is simply not sustainable to work 100 or 130 hours a week over and over again.

And, for the record, the only time to be strategic about bathroom breaks is when on a road trip (I'm assuming you share my lack of fondness for gas station bathrooms.)

Hustling to nowhere

Sure, under exceptional circumstances, it's possible to slog it out for a week or two or three. But soon, we run into the limits of our human minds and bodies. Without restorative breaks, our creative juices stop flowing, and we become not just increasingly less efficient in our pursuits but more prone to error.

In short, the very thing long hours are meant to accomplish—extended personal productivity—is what suffers when the balance from work is tipped towards overwork.

Also, the hustle culture raises one fundamental question—what are we hustling towards?

To what end?

In an article in the New York Times, writer Erin Griffith refers to the performative workaholism that seems to have taken over our culture, especially in the Tech industry. She says that tech workers have subscribed to a rather extreme work ethic and belief:

Work is not something you do to get what you want; the work itself is all. Therefore, any life hack or company perk that optimizes their day, allowing them to fit in even more work, is not just desirable but inherently good.

Griffith uses the example of an SF-based entrepreneur who socialized only at networking events or only read business books, rarely doing anything that didn't have a "direct R.O.I (return of investment)" for his company.

What are we running from?

Busyness is an escape mechanism from dealing with all the existential problems about life itself; questions such as who we are, what our purpose is, etc. Mindless productivity can help us live in a state of denial. It allows us to continue to work on unimportant matters instead of confronting the harder truths of life.

But does it make us happier in the long run?

No prizes for guessing that the answer is a resounding "No."

According to Bronnie Ware, author of the international bestselling book Regrets of the dying, the following are the number one and number two end-of-life regrets of people:

1. I wish I'd had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.

2. I wish I hadn't worked so hard.

Personal productivity done right

Personal productivity was never meant to turn us into one-trick ponies; the whole premise was to make us efficient at doing things that were important to us.

The truth is, hustling doesn't really fit the bill.

So, the first and most important step is to define for yourself what a well-lived life means. To you. And then, you can go about optimizing your life using productivity tools.

Chasing personal productivity is like chasing the unicorn of perfection. You are bound to fall short. That's a given. But, as Franklin described earlier, you will be happier overall if you at least attempt to stay productive. And the trick is to reset expectations of how productive your day will be.

Take pleasure in small wins

If you wait to feel good until you publish the next N.Y. Times bestseller or make it to Fortune's list of 100 most influential people in the world, you'll be waiting for a long time. Possibly, forever.

Instead, celebrate the small wins.

Give yourself permission to feel productive after you've deleted fifty of those accidental screenshots that managed to save themselves as photos on your phone. Rejoice when you can use the side door to the garage again because you finally emptied out the cat litter.

Any little tasks you can do that make your day and life a little bit better are worth the tag of "productive work."

Everyone needs to make lists

A friend had asked me to take her trash out when she had gone on vacation. "Of course! Consider it done," I said. And promptly forgot about it. A week later, literally at 3 a.m., my brain finally remembered the trash. Yikes! She was back in town by then.

My only options then were to either secretly steal her trash container (and risk making it to the "Ring caught on camera viral neighborhood newsfeed) or come clean and admit that I, a wannabe Marie-Kondo incarnate, had dropped the ball on being organized because I had a memory lapse.

A predicament I could have avoided had I just added her request to a list.

Lists are good. They help structure our inherently unstructured lives. But more than that, they prevent our brains from becoming overwhelmed by acting as repositories for the million things we commit to, ought to, or want to do.

Avoid hyper-scheduling

A lesser-known life fact:

Unlike most organic things in life, like plants and humans that shrivel and die if you don't feed and nurture them, your inbox has a tendency to grow on its own.

(Mostly because we are not islands, and other people keep throwing stuff at us all the time.)

Life does not stop. If you have a perfect day scheduled, I can guarantee you that there will at least be one significant unforeseen threat to your schedule.

Overloaded and overly scheduled days are just disasters waiting to happen. Truly productive people intentionally have holes in their schedules to respond to unforeseen crises.

That said, not everything that gets thrown your way at the last minute deserves equal attention. Learning to separate the important from the urgent is a vital skill not just for productivity but to keep you sane.

Get out and wander

There is no doubt that movement, especially leisurely movement, fosters creativity. Getting out and letting the mind wander without subjecting it to the constant pressure to check things off a to-do list can significantly enhance your personal productivity.

Rest days are key

The saying, "Don't just sit there, do something," embodies how we view productivity. Any idle time is considered wasted time. But, the world's greatest investor, Warren Buffett, used this baseball analogy to preach the contrary.

The lesson is to not swing at everything…The trick in investing is just to sit there and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one right in your sweet spot. And if people are yelling, 'Swing, you bum!,' ignore them.

In short, "Don't just do something. Sit there and think about what you actually need to do" is better advice, especially regarding personal productivity.

In an interview published in the Guardian, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang author of Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, said this about email and smartphones:

We are discovering that these technologies do not automatically make us more productive or give us more time with our kids. Rather, they have tended to grind work down to a fine powder that spreads out right through our day.

He urges us to

Make more time in our lives for leisure in the classic Greek sense, not playing a lot of video games.

Productivity tools

Even if you have managed to buck the trend, march to your own beat, and step off the hedonic treadmill, there still is a lot of value in adopting some of the common productivity tools and techniques. After all, regardless of whether you are in the rat race or not, the whole world is vying for the one resource that is in limited supply: your time. So, any techniques that can help protect your time are worth your consideration.

So next time you hear someone extol the values of zero inbox, the magic of turning your phone notifications off, or even getting a better chair, rein in your skepticism and try not to roll your eyes. Hype aside, some of these tools make your life less frantic and improve your physical and mental health in the long run.

Finally

Sometime in the last decade, every self-improvement platform that had already urged people to eat kale, meditate, and kill it at CrossFit, also added the call to "stay productive." Unfortunately, the bit that got left out was a clear definition of what it means to be productive. As a result, we are too busy hustling away, buying productivity apps, and implementing personal productivity processes before we've had the time to define what it is we're trying to optimize.

Personal productivity is not about working long and hard. Nor is it about cramming every available second of every day with activity. Instead, it is about getting what's important to YOU done efficiently and consistently.

Nothing is less productive than to make more efficient what shouldn't be done at all. Peter Drucker.